Compromises of the Constitution

When the Constitutional Convention began, Edmund Randolph and James Madison put forward the Virginia Plan that called for a government much like the one we have today. There would be three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial.

The legislative branch would be made up of two houses; however, unlike our national government today, representation in both houses would be based upon a state’s population. This plan differed from the Articles of Confederation that gave each state one vote in Congress regardless of its population.

Smaller states like Delaware and New Jersey objected to this, saying that large states would easily outvote them if the number of votes were based on population.

After weeks of debate, William Patterson of New Jersey put forth a plan that called for three branches including a legislature with only one house where each state would have one vote. The New Jersey Plan with a single house legislature and equal representation was more like Congress under the Articles.

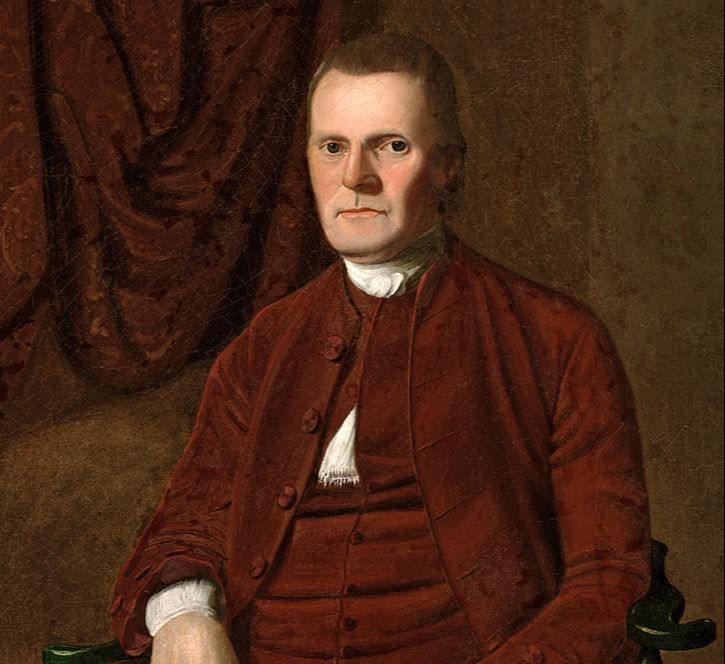

The convention was deadlocked and appeared ready to fall apart when Roger Sherman proposed a compromise. Sherman’s proposal has come to be known as the Great Compromise. It called for a Congress with two houses (also known as “bicameralism”) – the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The Senate would give equal representation to all of the states which satisfied the small states. The House of Representatives would be based on a state’s population which satisfied the large states. Delegates narrowly approved Sherman’s compromise on July 16, 1787.

Since representation in the House of Representatives was to be based on population, a debate arose over whether enslaved people should be counted in a state’s population. According to James Madison’s diary, the issue of slavery was the most divisive subject at the convention. A few of the attendees argued forcefully against slavery, especially John Dickinson, a Quaker representative from Pennsylvania.

Others agreed that slavery was inconsistent with the principles of the Declaration of Independence, but knew that there was little chance of abolishing it. After all, if those opposed to slavery insisted on its abolition, slave state delegates could have walked out of the convention and formed their own nation with a pro-slavery constitution. Washington and other Founders hoped that slavery could be eliminated from the United States once a strong union was formed.

The next issue had to do with slavery and population. States with enslaved people wanted to count all of them in their state’s population, because that would yield more representatives in Congress. The opponents of slavery, noting that slaves had no rights of citizenship including the vote, argued that enslaved people should not be counted at all for purposes of representation.

The compromise that settled the issue of how to count slaves for representation in the House came to be known as the Three-fifths Compromise. The compromise was to count three-fifths of the state’s enslaved population in the total population.

In other words, for every five enslaved men, three would be added to the population count used to determine representation in the House of Representatives.

The delegates also disagreed over the slave trade. By the time of the Convention in 1789, some northern states had outlawed slavery. These states wanted a ban on the slave trade included in the Constitution. Southern slave states objected, claiming that the slave trade was important to their agricultural economy.

Finally, the two sides compromised by allowing the slave trade to continue for 20 years after which time the Congress could regulate it. In 1808, Congress abolished the slave trade.