Japanese American Internment During WW2

Asian Americans faced bigotry and hostility since their first arrival in the United States, especially on the West Coast. As a result, the American government took actions against them. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion banned immigrants from China. After anti-Asian race riots across the Pacific Coast in 1907, a Gentleman's Agreement between Japan and the U.S. effectively ended Japanese immigration. The Immigration Act of 1924 banned all immigration from Japan and other "undesirable" Asian nations.

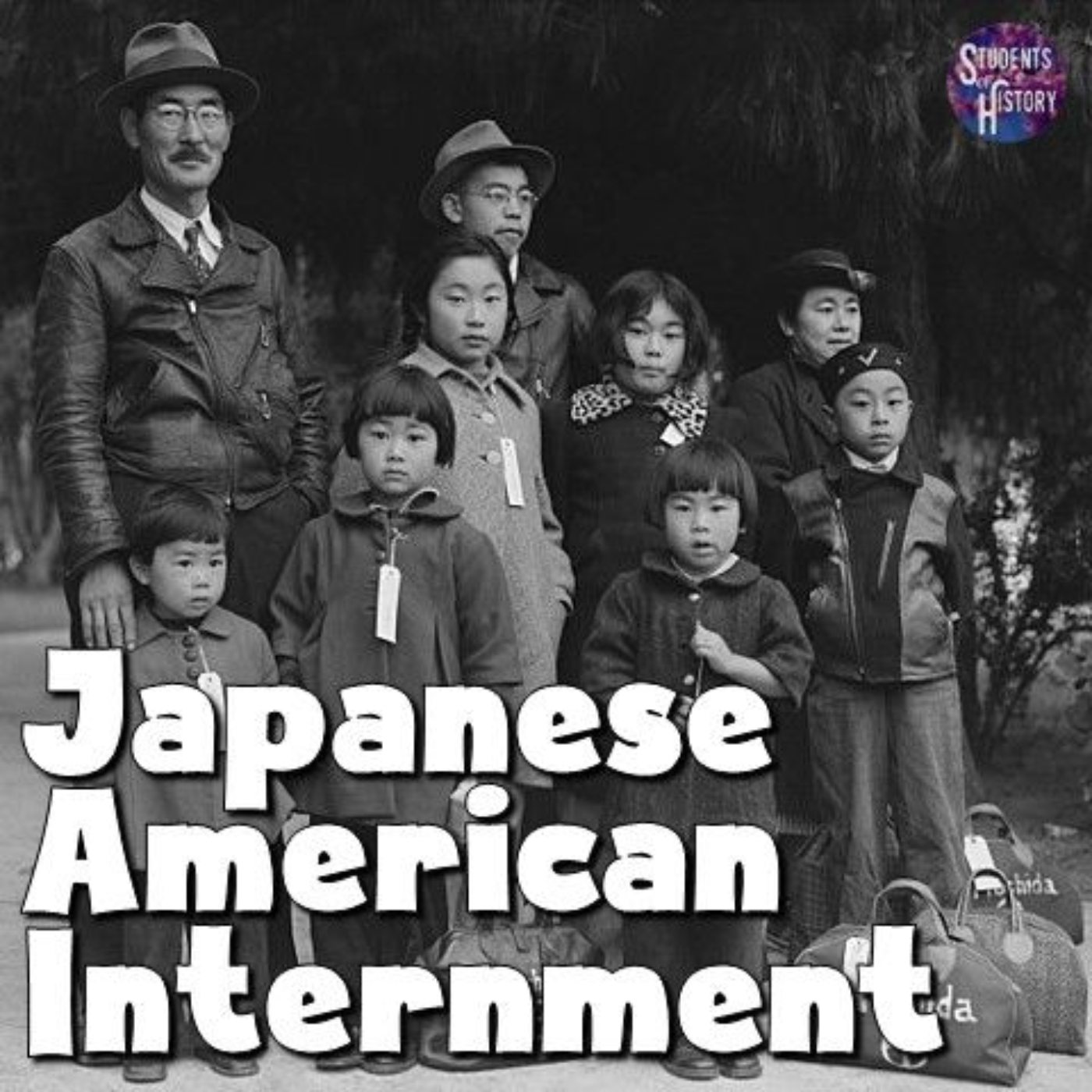

In 1941, there about 127,000 Japanese Americans living in the continental United States. Most were on the West Coast and well over half were "Nisei" or second generation, American-born Japanese with U.S. citizenship.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, American public opinion initially stood by their Japanese American neighbors. Many Americans believed that their loyalty to the United States was unquestionable. However, as the war effort ramped up, racial prejudice led public opinion to turn against Japanese Americans.

They often became victims of glaring racism. Neighborhood signs threatened them to "keep out" and many Japanese-owned businesses were vandalized.

Some feared that Japanese Americans would work as spies for the Japanese government. These unfounded rumors spread and soon President Franklin D. Roosevelt was impelled to act. On February 19, 1942, the President signed of Executive Order 9066. This authorized military commanders to designate the West Coast as a "military area ... from which any or all persons may be excluded."

Eviction from the West Coast began in late March, when Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1 gave 227 Japanese American residents of Bainbridge Island, Washington just 6 days to prepare for their "evacuation" directly to Manzanar, one of the concentration camps set up in California.

Eventually, nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans would be sent to one of 10 different concentration camps in California, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, and Utah. The government called them “War Relocation Camps” and most sent to one were held until World War 2 ended in 1945.

The conditions within the camps were horrible. They were located in remote areas, with an inadequate food supply, and often overcrowded. They featured makeshift schools, barracks for housing, and work facilities.

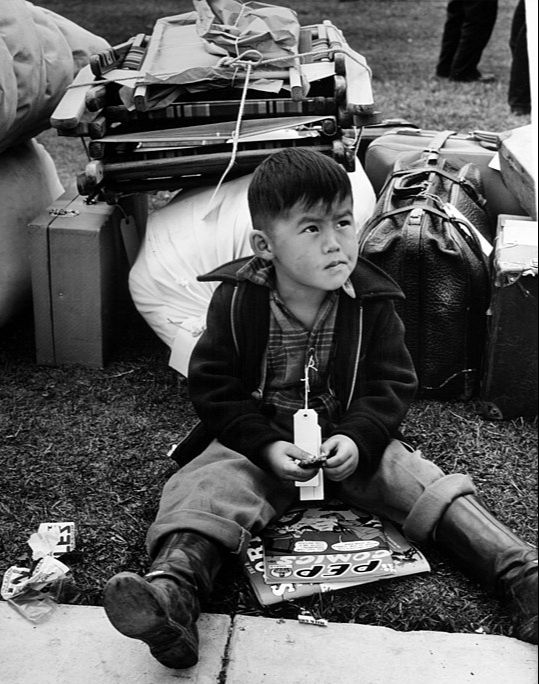

Over 17,000 of those forcibly relocated to camps were children under the age of 10. Growing up in the internment camps, young children felt isolated and singled out simply because of their ethnicity.

It most certainly felt like a prison to them and they came to realize as they got older that they had been let down by their country.

One of those interned was Fred Korematsu. He was born in Oakland, California in 1919 to Japanese parents who immigrated to the United States in 1905. He refused to go to a relocation center and was arrested. After being found guilty of defying the order he was sent to Topaz concentration camp, where he and his family were held from 1942-1945.

Korematsu appealed his guilty verdict all the way up to the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that relocation and internment was justified during circumstances of "emergency and peril".

It is now widely agreed that the internment of the Japanese Americans was not justified and was based solely on racism. Japanese Americans did not pose any credible threat to the country. In fact, more than 12,000 Nisei served in segregated Japanese American combat units, most famously the 442nd Nisei Infantry Regiment.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan officially apologized for Japanese internment and authorized a payment of $20,000 to each living former detainee. Legislation admitted that the government's actions were based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." More than $1.6 billion was paid in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated.